The Vietnam War, as Seen by the Victors

How the North Vietnamese remember the conflict 40 years after the fall of Saigon

HANOI, VIETNAM—Forty years ago, on April 30, 1975, Nguyen Dang Phat experienced the happiest day of his life.

That morning, as communist troops swept into the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon and forced the U.S.-backed government to surrender, the North Vietnamese Army soldier marked the end of the war along with a crowd of people in Hanoi. The city was about to become the capital of a unified Vietnam. “All the roads were flooded by people holding flags,” Nguyen, now 65, told me recently. “There were no bombs or airplane sounds or screaming. The happy moment was indescribable.”

The event, known in the United States as the fall of Saigon and conjuring images of panicked Vietnamese trying to crowd onto helicopters to be evacuated, is celebrated as Reunification Day here in Hanoi. The holiday involves little explicit reflection on the country’s 15-year-plus conflict, in which North Vietnam and its supporters in the South fought to unify the country under communism, and the U.S. intervened on behalf of South Vietnam’s anti-communist government. More than 58,000 American soldiers died in the fighting between 1960 and 1975; the estimated number of Vietnamese soldiers and civilians killed on both sides varies widely, from 2.1 million to 3.8 million during the American intervention and in related conflicts before and after.

In the United States, the story of America and South Vietnam’s defeat is familiar. But North Vietnam’s war generation experienced those events differently, and several told me recently what it was like to be on the “winning” side.

Decades after what’s known here as the “American War,” Vietnam remains a communist state. But it has gradually opened to foreign investment, becoming one of the fastest-growing economies in East Asia. As an American who has lived in the Vietnamese capital for three years, I rarely hear the conflict discussed. At Huu Tiep Lake, which is located at the quiet junction of two residential alleys, vendors sell fresh produce without glancing at the wreckage of a B-52 that was shot down there in 1972 and still juts out of the water as a memorial. Nor do many passersby stop to read the plaque that describes, in both English and Vietnamese, the “outstanding feat of arm” that brought down the bomber of the “US imperialist.”

It’s rare to find such marks of the communist triumph on the streets of Hanoi. Kham Thien Street, a broad avenue in the city center, bustles with motorbikes and shops selling clothing and iPhones. There’s little evidence that some 2,000 homes were destroyed and nearly 300 people killed nearby during the 1972 “Christmas bombing,” the heaviest bombardment of the war, ordered by the Nixon administration to force the North to negotiate an end to the conflict.

“There were body parts everywhere,” recalled Pham Thai Lan, who helped with the relief effort as a medical student. It was the first time she’d seen so many corpses outside the hospital. Now a cheerful 66-year-old, she grew somber as she talked about that day. As Nguyen, the veteran, told me: “Talking about war is to talk about loss and painful memories.”

* * *

When I talk to Hanoi residents about their experiences “during the war,” they often ask me which one I mean. For members of Nguyen’s generation, the American War was one violent interlude amid several decades of fear and conflict, falling between a fight for independence from the French beginning in the 1940s and a month-long border war with China in 1979.

Vu Van Vinh, now 66, was five years old when the French left their former colony in Vietnam in 1954. By then he had learned to be wary of the French officers who patrolled the streets of his town in Quang Ninh province, northeast of Hanoi. “Whenever I saw foreigners, I felt scared,” Vu told me. Ten years later, the United States began bombing North Vietnam.

The first time he saw a B-57, he gaped skywards, trying to make sense of it: “Why is a mother airplane dropping baby airplanes?” A minute later, he said, “Everything was shaking. Stones were rolling. Houses were falling.” He raced home, panicked and confused: “I still couldn’t register what it was in my mind.”

With U.S. bombers sweeping over the town nearly every week, Vu and his family moved to a mountainous area a few kilometers away, where limestone caves served as bomb shelters. Vu once discovered the body of a man who hadn’t made it inside the cave in time. “I turned him over,” he said. “His face had exploded like a piece of popcorn.”

Vu was drafted into the North Vietnamese Army but was discharged after a month of training due to hearing problems. His older brother was also drafted and ended up serving in the South. At home, Vu and his parents could only follow the progress of the war through government-controlled radio and newspapers. “Cameras belonged to the country, so they would give them to only a few journalists to take pictures of battle,” explained Nguyen Dai Co Viet, a professor at Vietnam National University. Restricting access to cameras enabled the government to control, to some extent, how the war was understood. “My bosses instructed me to shoot anything showing that the enemy would lose,” former war journalist and documentary filmmaker Tran Van Thuy told me.

In rural Quang Ninh, Vu and his family heard snippets of news—how many airplanes were shot down that day, who was winning, what the “cruel American wolves” were doing in various areas of the country. There was little explanation of why the violence was happening. “People didn’t talk about the meaning of the war,” he said. “We were really confused why the Americans tried to invade our homeland. We hadn’t done anything to them.”

I asked Vu if the Vietnamese had understood that the United States perceived communism as a threat.

“People didn’t even know what communism was,” Vu told me. “They just knew what was going on with their lives.”

* * *

My conversation with Vu underscored a key difference between how I learned about the war, growing up in the United States in the 1990s, and how the Vietnamese I’ve spoken with in Hanoi understood it while living through it. “The U.S. tried to inscribe the war in Vietnam into its Cold War campaign,” Thomas Bass, a historian and journalism professor at University at Albany, State University of New York, told me. “North Vietnamese were evil communists, and the free and independent people of the South were to be protected.”

But I’ve rarely heard Vietnamese speak in these terms. Nguyen Dang Phat, the North Vietnamese Army veteran, told me: “On the news at the time, they said that this war was a fight for independence. All the people wanted to stand up and fight and protect the country. Everyone wanted to help the South and see the country unite again.” Do Xuan Sinh, 66, who worked in the military-supply department, placed the American War in the context of a long history of struggle against foreign interference, from “fighting the Chinese for 1,000 years”—a reference to the Chinese occupation of the country from 111 B.C. to 938 A.D.—to the war with the French. “All Vietnamese understood that the [Communist] Party helped Vietnam win independence from France. Then in the American War, we understood the party could help us win independence again.”

Tran Van Thuy, the former war journalist, told me that it would be “difficult” to find anyone in North Vietnam who was against the war, in part due to what he called the “strong and effective” propaganda machine. “You would find people queuing around to buy party newspapers or gathering around loudspeakers to hear the news,” he said. “People were hungry for information and they believed what they heard. There was a strong national consensus.” In the South, by contrast, people had access to international news on the radio and popular ballads mourned the sadness of war—perhaps reflecting more ambivalent attitudes there. Nor was there any North Vietnamese equivalent to the organized and highly visible anti-war movement in the United States. “America and Vietnam are not the same,” Nguyen Dai Co Viet, the VNU professor, told me. “Our country was invaded, and we had to fight to protect our country.”

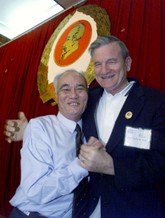

Vietnam War Bill Dyke (R) hugs

retired North Vietnamese Army

soldier Mai Thuan at a meeting

between veterans in Hanoi in

2000.

Those who did speak out against the war put themselves in danger. A former political prisoner who asked that his name not be used told me that when he started an organization to protest the war, he was jailed for several years. As a teenager in Hanoi, he had listened illegally to BBC radio broadcasts. When the fighting started, he gathered a handful of friends to print pamphlets saying, as he told me, that “the purpose of the war was not for the benefit of Vietnamese people, just for the authorities in the North and South."

“Others called it the American War, but I saw it as a civil war between the North and South of Vietnam. America only took part in this war to support the South to fight communism,” he said. This regional divide persists. “The country has been unified for 40 years, but the nation is yet to be reconciled,” said Son Tran, 55, a business owner in Hanoi with relatives in the South. “Vietnamese media have shown many pictures of American soldiers hugging North Vietnamese soldiers. But you never see any pictures of a North Vietnamese soldier hugging a South Vietnamese soldier.”

* * *

On May 1, 1975, Vu and six others marked the end of the war with a party, pooling their ration stamps to buy a kilogram of beef and filling out the meal with tofu. They didn’t have a cooking vessel, so they poured water into powdered milk cans and boiled the meat inside, “like [a] hot pot,” Vu said. His brother was not there; his body, like those of an estimated 300,000 Vietnamese soldiers, still hasn’t been found. Government-run TV channels still broadcast the names and photographs of the missing every week, along with their relatives’ contact information.

The festive mood as wartime ended was followed by what Bui The Giang, an official in Vietnam’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, called the “disastrous” decade of the 1980s. With untrained officials making economic decisions and the state controlling every sector, growth was stagnating, inflation was high, and poverty was rampant. Bui estimated that one-fifth of the population was starving. “We only had four hours of electricity every day,” Vu’s daughter Linh Chi, now in her 30s, recalled. “Until I was five or six, I didn’t even see a TV.”

But since the market reforms of the late 1980s, life has gradually improved. After years of steady economic growth, the country's poverty rate fell from almost 60 percent in the 1990s to about 20 percent in 2010. Today, Linh Chi owns a trendy Mexican restaurant in Hanoi. Young Vietnamese and expats jostle for motorbike parking space, Instagramming their $6 burritos.

In the meantime, a generation has grown up with no experience of the war. A 56-year-old banh mi vendor in Hanoi who gave her name as Thuan complained about how much society has changed: “Young people today are a little bit lazy. They are not willing to experience poverty, like being a waiter or a housemaid. They didn't experience war, so they don't know how people back then suffered a lot. They just want to be [in a] high position without working too much.”

Her son, a burly 26-year-old limping from a post-soccer brawl, interrupted to ask for a banh mi. Thuan split a roll with scissors and spread it with a layer of pâté.

“She keeps talking on and on about the war. It's really boring, so I don't really listen,” he said.

Nguyen Manh Hiep, a North Vietnamese Army veteran who recently opened Hanoi’s first private war museum in his home, remains preoccupied by the conflict and his need to teach the younger generation about it. He displays artifacts from both sides, collected over eight years of fighting and two decades of return trips to the battlefield. The items range from American uniforms and radio transmitters to the blanket his superior gave him when he was wounded by a bullet. He showed me a coffee filter that one of his fellow soldiers had made from the wreckage of an American plane that had crashed. We drank tea in his courtyard, surrounded by plane fragments and missile shells.

“I want to save things from the war so that later generations can understand it,” he told me. “They don’t know enough.”