“People don’t realise what they’ve lost,” says Candy Nguyen as she peers through the locked gates of what was until recently the historic Ba Son shipyard. “Many don’t even know what was here before.”

Ho Chi Minh City’s oldest and most important maritime heritage site is hidden from the street by high blue hoardings peppered with slogans such as “Never still” and “Redefine the skylines”.

It is currently the largest development project in the city’s central District 1 neighbourhood, with a cluster of partly constructed 50-storey apartment blocks jutting above the fence. Volunteers for the Saigon Heritage Observatory, such as Nguyen, have not been allowed in since building work began. All believe the shipyard – founded in the 18th century by Gia Long, who would go on to become emperor – and its unique industrial architecture have been completely destroyed.

Renders for what will replace it show rows of upmarket townhouses between the tall glass and steel towers, as well as a yachting marina on the Saigon River: luxury living for the few.

“It used to be so beautiful,” says Nguyen as we walk the Ba Son perimeter, a constant stream of scooters flowing around us. “I cried when I first heard we had lost the trees. My mother used to take me this way to school and the trees used to give shade and oxygen. People used to collect tamarind and sell it … until last year when they cut the trees down.”

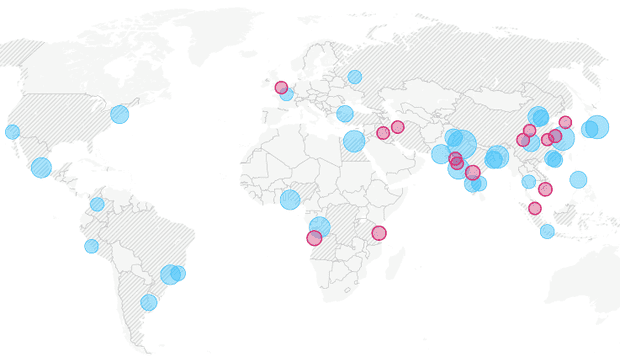

Q&AWhere are the next 15 megacities?

Show

By 2035 another 15 cities will have populations above 10 million, according to the latest United Nations projections, taking the total number of megacities to 48.

Guardian Cities is exploring these newcomers at a crucial period in their development: from car-centric Tehran to the harsh inequalities of Luanda; from the film industry of Hyderabad to the demolition of historic buildings in Ho Chi Minh City.

We'll also be in Chengdu, Dar es Salaam, Nanjing, Ahmedabad, Surat, Baghdad, Kuala Lumpur, Xi'an, Seoul, Wuhan and London.

Read more from the next 15 megacities series here.

Ho Chi Minh City (known as Saigon until reunification in 1976) has long had a reputation for being international and cosmopolitan – particularly compared with the one-party state’s political capital, Hanoi, in the north. As the economic capital of communist Vietnam it has always been the place to make money, but with a population of 8.1 million – set to rise above 10 million by 2026, according to the latest UN estimates – the pace of change in this dynamic city has accelerated.

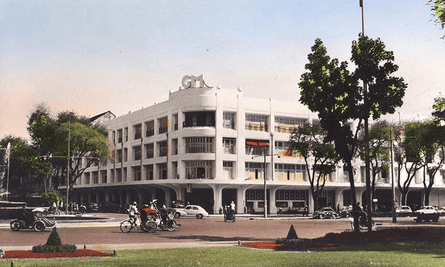

Gone, gone, gone, going …? Clockwise from top left: the Charner store, the art deco 213 Dong Khoi apartments, the navy exchange and a colonial-era government building. Photographs: Historic Vietnam/Tom Hricko

Heritage experts say virtually no historic buildings are safe from the wrecking ball. Ba Son is being transformed into Golden River, an upmarket development marketed as a “city within a city”. It is a project from Vinhomes – part of the huge and ubiquitous Vingroup conglomerate, which has fingers in everything from real estate to retail and hospitality to health care. The chairman, Pham Nhat Vuong, who founded the company as an instant noodle producer in Ukraine in the 1990s, was Vietnam’s first billionaire. He remains its richest man.

Among the villas, golden fences and palms of one nearly completed section of Golden River, a billboard promises a new branch of Vinschool and signs announce Vinmart convenience stores. All that is left of the former shipyard is a pair of barnacled anchors, a cannon and some planks of aged timber – now decorating the upmarket Myst hotel. “Ba Son had a rich history but they have destroyed all of it,” says Nguyen. “We are losing the character of the city.”

A mile to the north-east lies another Vingroup development, Central Park, with the Landmark 81 skyscraper at its heart, surrounded by 17 apartment towers. This so-called supertall became the highest building in Vietnam, and 14th highest in the world, when it completed last year.

The Central Park development, with the Landmark 81 skyscraper at its centre. Photograph: JethuynhCan/Getty Images

Shoppers entering the Vincom Center mall at its base are greeted by a blast of air-con and a glitzy showroom featuring a bright yellow Lamborghini Huracán supercar and three different models of Bentley. There is a Vinmec hospital, a Vinpro electronics store and a Vinsmart phone dealer. Vinmarts are located in the base of every tower.

While Central Park was largely built on reclaimed land and vacant lots, anything built in the centre is likely to lead to the demolition of a historic building.

No official public records are kept, but it is estimated that more than a third of the city’s historic buildings have been destroyed over the past 20 years.

In 1993 the Centre for Prospective and Urban Studies, a Franco-Vietnamese urban research agency, classified 377 buildings in the central districts 1 and 3 as heritage sites. By 2014, 207 of those had been demolished or altered beyond recognition. “For the past four years it has been continuing for sure,” says one urban planner involved in the original inventory, who did not want to be named.

The People’s Committee, which runs the city, is currently dividing around 1,000 historic buildings into three classifications: class 1, which is protected; class 2, where the owner can build on the lot but cannot destroy the old building; and class 3, which can be demolished.

“It is sad, but the owners of class 3 are seen as the winners,” says the planner. “Generally they are after immediate profit and people want modernity, cleanliness, air-conditioning … they’re not interested in preserving old tiles. They see that the owner next door demolished to build a 32-storey office with restaurant and luxury flats and they think, why can’t I?”

Before and after: Another historic building bites the dust (left) and the park and building destroyed to make way for the Vincom Center (right). Photographs: Historic Vietnam

A stroll down the elegant Dong Khoi street illustrates the scale of change. The art deco and modernist buildings of the early 20th century fell into decline during the Vietnam war, but the area has undergone a revival of late with stores by Gucci, Dior and Louis Vuitton.

Destruction, however, is never far away. The once-prestigious art deco apartment building at 213 Dong Khoi (mentioned in Graham Greene’s The Quiet American) was demolished for a new government office. One block west, the 1924 Charner department store (latterly the Tax Trade Centre) was knocked down to make way for the city’s long-delayed metro. Assurances were given that its grand Moroccan-style staircase and intricate tiles were to be removed and preserved, but heritage groups believe them to have been destroyed.

Next door to the 19th-century Hotel Continental, where Greene used to drink and write, the six-storey Eden Building (used as a media centre during the Vietnam war) featured the distinctive curved corner style particular to modernist buildings along Dong Khoi, and housed a colonial-era cinema and arcade – until it was demolished in 2009 for a Vincom shopping mall. Only one art deco apartment block survives on Dong Khoi, currently inhabited by a warren of small retailers and workshops, its shaky old elevator caked in dust. It, too, is slated for demolition.

The city’s modernist heritage may be next, says the architectural historian Mel Schenck.

The skyline from an apartment in the Golden River complex. What remains of the historic Ba Son shipyard can be seen at the bottom right of the image. Photograph: Tan Le/Getty

Schenck estimates that 70-80% of the city is built in modernist style, much of it by noted Vietnamese architects such as Ngo Viet Thu, who designed the Independence Palace. If you pick a classic “shophouse” street at random and look up, the majority of the top floors are modernist. “There is so much of it that it’s become ordinary and people don’t even think about it,” he says. “When I see awnings and junk around a house, that’s good, because that means the building is being well used and isn’t in as much danger of being demolished. If the house is cleaned up, it’s not a good sign.”

Even being designed by Ngo Viet Thu himself is no protection. A villa of his in District 3 is currently vacant apart from a live-in caretaker. “It’s on a hot street,” says Schenck. “There’s lots of land. It’s going to go.”

Ngo Viet Thu’s son, Ngo Viet Nam Son, is also an architect, and lives and works between Ho Chi Minh City, the US and Canada. He believes his hometown must learn from the mistakes made by other fast-growing Asian cities before it is too late.

“We’re not the only city to experience this growth, and we should learn from these experiences,” he says. “But this city hasn’t taken that lesson yet. In Ba Son, they could have made a very nice area, a cultural and green space for the city – something like Pier 59 in New York, or Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco – but instead they destroyed it.

“Developers don’t realise that when they destroy historic buildings they are losing a potential economic gain, and if you consider tourism, then people want to see the old city to get a sense of place. Preservation can contribute to economic value.”

Critics say the historic centre is increasingly filled with generic architecture which could be anywhere in Asia. Photographs: laranik/Alamy/Rwp Uk/Getty/Ngoc Nguyen Quang/Getty/EyeEm

He looks to Shanghai, which shares similar geography – a historic centre facing what was mostly vacant land across the river – and political conditions. There, the historic centre is largely protected, with the Pudong marshland east of the river has been developed as the financial district.

“We should preserve District 1 as our old downtown – some new building, but the priority should be to preserve,” he says. “Then Thu Thiem in District 2 over the river can be the international financial district.”

Instead, Ho Chi Minh City has two separate masterplans, with the one for the historic west foreseeing a wall of skyscrapers marching down the river. The new developments are often built on raised land to protect them from flooding, while ironically blocking rainwater from flowing freely into the river and so causing more floods elsewhere.

They also do not provide much in the way of public space. A new green space in the Central Park development, also built on land reclaimed from the river, is watched over by security guards who ask if users are residents. There is a ban on unaccompanied children under 12 and pets, and signs warn people to safeguard “etiquette, order, safety and aesthetics”.

Amid all the concrete and glass, there appears to be a belated appreciation of heritage among the city’s younger people. “Vintage” cafes are popular, even if they are often located inside modern air-conditioned buildings, as are vintage dresses and fashions.

“Heritage is trendy now, but I worry it is just a bubble,” says Nguyen. “It may be popular for a year but then I don’t know who will be with us after that.

“Ultimately I am optimistic that more people will learn and become interested and get involved – but I do feel frustrated that sometimes people just don’t care.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, and explore our archive here