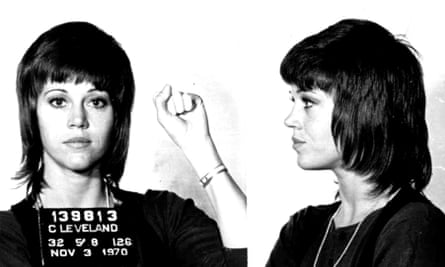

The first time I was ever arrested, I was picked up for smuggling drugs into the US from Canada. They were vitamin pills, but that didn’t seem to matter to the police officer in Cleveland, who mentioned that his orders had come from the Nixon White House. It was 1970. I had just started a campus speaking tour protesting against the Vietnam war, and was under surveillance by the National Security Agency. I raised my fist for the mugshot, and after a night in jail, they let me go.

I think the idea was to discredit my opposition to the war, and maybe get my speeches cancelled. Instead, students turned up in their thousands. My first arrest wasn’t for an act of civil disobedience, exactly, but the lesson I took away from that surreal experience was just how powerful it can be to set your ideals against the machinery of the state. Half a century later, it still works. And, as the extraordinary activists who tell their stories here attest, it remains an indispensable means of being heard by those who would prefer to ignore us.

Today, the climate crisis requires collective action on a scale that humanity has never accomplished, and in the face of those odds a sense of hopelessness may occasionally descend. But the antidote to that feeling is to do something. The question is: what? Changing individual lifestyle choices like giving up meat and getting rid of single-use plastic won’t cut it when time is not on our side. We need to go further, faster. Instead of changing straws and lightbulbs, we need to focus on changing policy and politicians. We need large numbers of people working together for solutions that work for the climate. Nonviolent civil disobedience can help to mobilise that movement. At 83, I’m still ready to get arrested when the occasion demands it.

In 2019, for example, I was arrested four times. I had been inspired by the global rising of Extinction Rebellion, the Sunrise Movement, and Greta Thunberg. Young people like Greta were calling on older generations to step up, and, well, I’m definitely older. It made sense to me: why should the burden of fixing this problem be on those who didn’t create it? In the same year, almost 400 scientists from more than 20 countries called for civil disobedience, arguing that “the continued governmental inaction over the climate and ecological crisis now justifies peaceful, nonviolent protest and direct action, even if this goes beyond the bounds of the current law”. I thought: maybe if I could get arrested in my 80s, it would get noticed. People might say: if she can do it, so can I.

With the help of Greenpeace, I launched Fire Drill Fridays. For four months we held weekly rallies in Washington DC followed by acts of civil disobedience including standing on the Capitol steps with banners, chanting, and blocking roads. We started small: about 16 of us walked up the steps of the Capitol, and turned to face the crowd of supporters and media that had followed us. There was something routine, almost ritualistic, about it: a line of 10 police officers had parted to let us take up our position. Then, as we had been told they would, they gave us the first of three warnings that we had to leave or face arrest.

We kept chanting and waving our signs. After the third warning, they stepped towards those of us who had stood our ground, and began to secure our hands behind our backs with white plastic cuffs. They stayed silent, almost stoic, as they led us to the vans. But we felt energised. I wasn’t scared: this was what I wanted to do, to put my body on the line, align myself fully with my values. There is something powerful about not knowing what’s about to happen, knowing that for a period of time you will have no control, and then to go ahead, and do it anyway.

I don’t mean to cast myself as a hero: the simple calculation is that my age and celebrity secures the kind of national and global press attention that the cause needs. That’s why I invited friends like Catherine Keener and Rosanna Arquette to join me. Another time, I shouted my acceptance speech for a Bafta while they led me away in cuffs. My publicist had hoped I’d come back to Los Angeles for it, but I’m told they liked the video in the auditorium.

Every Friday, people travelled to join us from all over the country. Most had never risked arrest before, and many told me they found the experience transformative. But as a famous white woman, I am under no illusions that my experience had much in common with that of a Black person without the international press in tow. We have to grapple with that dreadful reality if we want to be sure that what we’re doing is something more than tourism.

After a certain number of prior arrests, the police take a firmer line, and so, after my fourth, I wound up spending the night in jail. They shackled my hands and feet, and led me to a cell of my own: just me and the cockroaches. I got a baloney and cheese sandwich on white bread (I happen to like baloney). They stationed an officer outside “for my protection”, which freaked me out a little bit: given the lock, who could they be protecting me from but themselves? I used my sweater and scarf as a pillow, and put my coat over me, and tried to get some rest. When the officers were clanking up and down, making an awful lot of noise, I summoned all my upper-class-lady powers to ask if they could please be quiet so I could go to sleep. It didn’t make any difference.

The next day was an object lesson in how differently the state treats you depending on your race and position in the world: before I left, I was held with a number of other women, most of them Black, many seeming as if they needed proper care, not incarceration. I walked out, but they did not.

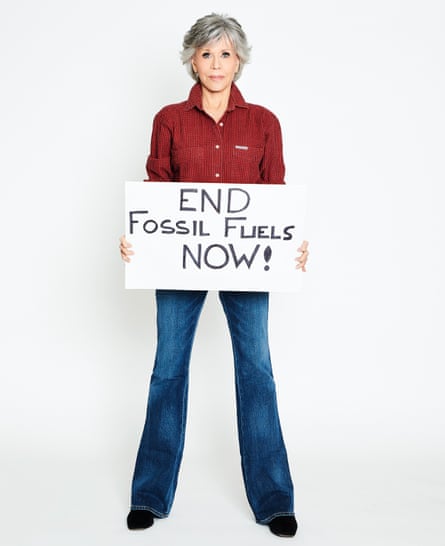

I hope that my disobedience can be a small contribution to the fight to press our governments to make immediate, bold policy changes that end all new fossil fuel development, ensure a just transition for affected workers and communities, and invest in the green energy systems to replace them. Hundreds of millions of lives hang in the balance with every half degree of warming we either enable or avoid, and right now world leaders are going in the opposite direction.

There is plenty of evidence that nonviolent civil disobedience can change the course of history. Think of the Boston Tea Party, Gandhi’s salt march and its role in securing India’s freedom from British colonialism, and the Montgomery bus boycott. Climate activists have spent years petitioning, writing articles and books, exposing officials to evidence, generating hundreds of thousands of texts and letters to officials, marched, lobbied: all to no avail.

This is what justifies nonviolent civil disobedience today – and it must be nonviolent if it is to secure public support. Research by the Yale Project on Climate Communication has found that 11% of Americans are alarmed by the climate crisis, but haven’t campaigned because nobody has asked them to. Around 10% of Americans aged over 18 are ready to engage in nonviolent disobedience, but have never been asked to do that, either. Well, it’s time to ask. Fire Drill Fridays started with a handful of arrests, and ended with hundreds: since then, we have continued to reach out with virtual Fire Drills during the pandemic. We had 9 million viewers across all digital platforms in 2020; viewers we are educating about climate and inviting to action. It is the “Great Unasked” that must be mobilised now worldwide.

We have all seen documentaries of activists willing to break unjust laws, face hoses and police batons, and asked ourselves what we would do if put to the test. Now’s our time. This is our moment. We don’t all necessarily need to face the hoses or get arrested, but unprecedented numbers of us need to rise up and put relentless pressure on the leaders who will attend next month’s Cop26 summit in Glasgow. We are the last generation that still has a chance to force a course change that can save lives and species on a vast scale. Remember: the cure for despair is action. And if you can put yourself on the line, who knows who you might inspire?