Playboy, bon vivant and the last emperor of Vietnam, Bao Dai chafed at his role as France’s puppet

While Bao Dai, who died 20 years ago this week, enjoyed the high life in Hong Kong and elsewhere, he did try to play his part during Vietnam’s most violent and troubled years amid the two Indochina wars

Twenty years ago tomorrow, the last emperor of Vietnam died peacefully and without ceremony in a military hospital in Paris, aged 83.

Bao Dai, or the “keeper of greatness”, was the 13th and last monarch of the Nguyen dynasty, and more famous for his lurid and extravagant lifestyle – he was exiled in Hong Kong for several years – than for his statesmanship during some of the most turbulent and bloody years in his nation’s history, the years of the liberation war against the French and civil war between north and south.

“He became far better known for his leisure activities,” is how the New York Times put it in his obituary.

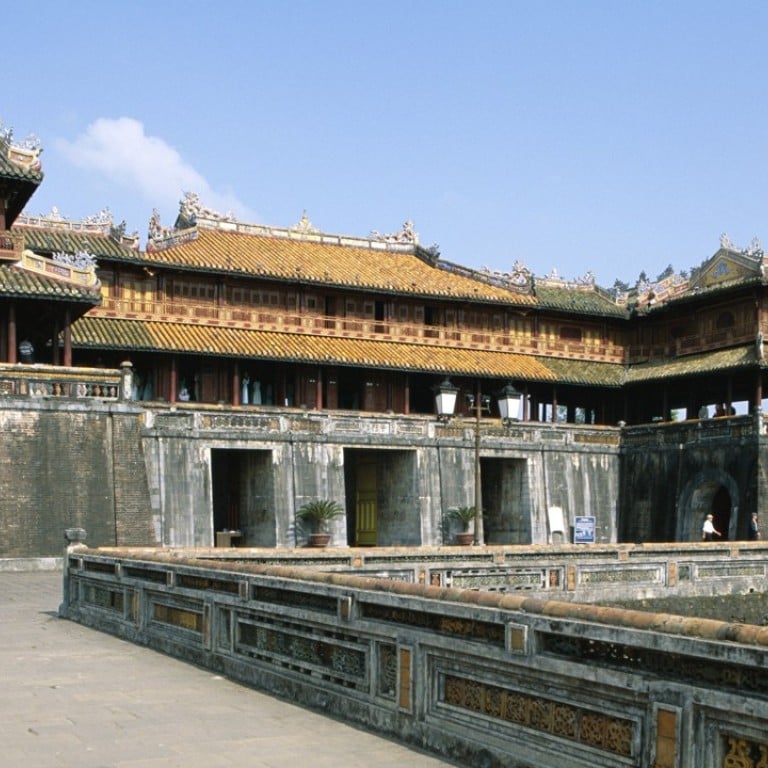

Born in 1913, within the walls of the magnificent Imperial Palace in the city of Hue, on the banks of the Perfume River, Bao Dai was educated in France and quickly developed a reputation as an adventurer, philanderer, hunter, movie fan, gambler and playboy.

History has not been especially kind to Bao Dai, who is commonly portrayed as a carefully trained pet monarch.

“The indolent puppet emperor,” as American journalist Stanley Karnow describes him in his book Vietnam a History (1983), was retained by his French masters (who had made Vietnam a protectorate in 1858) to counter rumblings of nationalism and anti-colonialism in French Indochina.

While alliances and deals were being brokered and civil war raged, Bao Dai was often away hunting ..., ... at his chateau in France or being entertained by ... hostesses in one of the more exclusive nightclubs of Tsim Sha Tsui

Bao Dai certainly enjoyed the finer things in life. In May, a gold Rolex watch he bought in the 1950s, while his country was being torn apart in the first Indochina war, sold for more than US$5 million at auction in Geneva. The so-called “Bao Dai watch” is a Rolex reference 6062, the most expensive and rarest model the Swiss luxury watchmaker made during that period.

While alliances and deals were being brokered and civil war raged, Bao Dai was often away hunting in the Vietnamese countryside, lounging by the pool at his chateau in France or being entertained by a protective posse of hostesses in one of the more exclusive nightclubs of Tsim Sha Tsui.

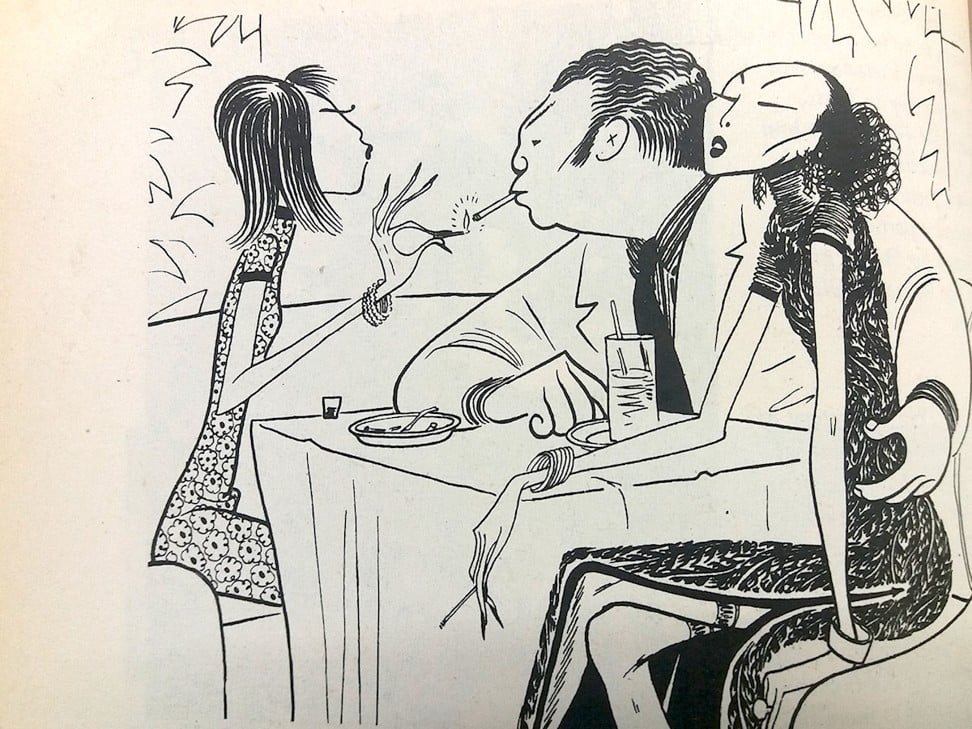

“A slippery looking customer rather on the pudgy side and freshly dipped in Crisco [cooking oil],” is how American satirist S.J. Perelman described Bao Dai after they met in just such a nightclub in 1947. The “keeper of greatness” was captured by cartoonist Al Hirschfeld, who was travelling with Perelman, and the image compounds the popular perception of the last emperor of Vietnam as an oleaginous and lascivious spoiled brat, addicted to opulence.

That said, some Vietnamese historians suspect that Bao Dai was not the legitimate heir to the throne. His father, Emperor Khai Dinh, who died in 1925, was widely assumed to be homosexual, or impotent, or most likely both. One theory suggests that Bao Dai was the son of the emperor’s aunt, and that his father was a senior French colonial court official.

Whatever the truth, compliance with colonial authorities was a more essential qualification than bloodline for a Vietnamese monarch. Royal recalcitrance was ignored or resulted in permanent exile to Reunion Island, the fate that befell Duy Tan, the 11th emperor.

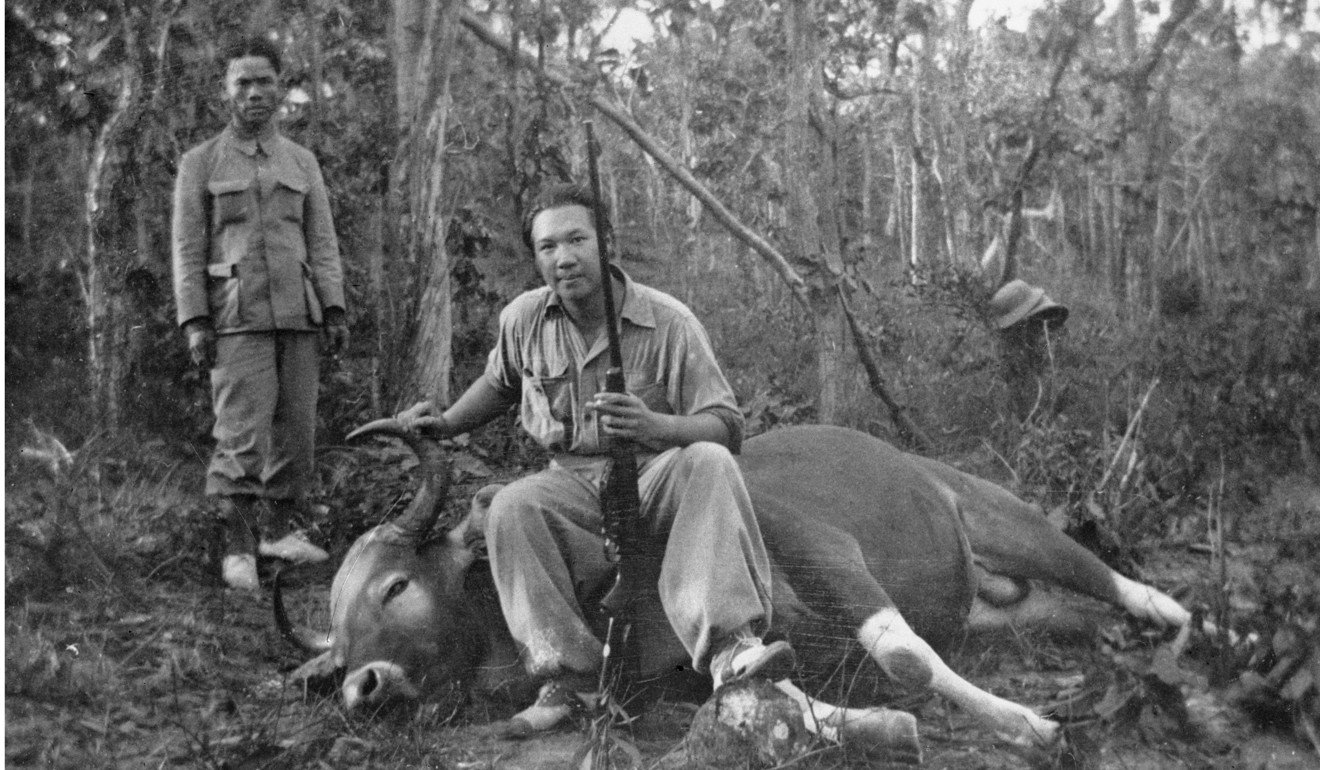

To make matters worse, Bao Dai is also accused of having single-handedly exterminated most of Vietnam’s indigenous tiger population during his frequent hunting expeditions, conducted from his hunting palace at the hill station of Da Lat.

Nestled amid a hillside forest overlooking the town, the “palace” is now a popular tourist attraction, though its architecture is unusual in a hill retreat favoured by the 19th-century French colonial elite, and more resembles a modest art deco public building in suburban London than the ostentatious fun palace of a playboy.

A large photograph of Bao Dai, looking suitably urbane and statesmanlike, looms over the fireplace in the sitting room, among many family photos.

Bao Dai married Marie-Thérèse Nguyen Huru ThiịLan in a lavish ceremony held at the Imperial Palace in Hue in 1934. She had been born in Gò Công, in the Mekong delta but, like many of the Vietnamese elite, was raised and educated as a Catholic in France.

She was given the title “Imperial Princess” and the new name Nam Phuong. The royal couple had five children (two boys and three girls) together, the eldest being Crown Prince Bao Long, who was born in January 1936.

Bao Dai’s bedroom, like the rest of the house, is tastefully furnished, with none of the ostentation one might expect. There are no tiger skin rugs, glittering chandeliers or gilded mirrors on the ceiling, but a balcony did allow the emperor to observe the moon. The sober style contradicts the popular narrative of a showy buffoon.

A glance through Hong Kong newspapers from 1947 to 1955 shows that the political machinations of Bao Dai and his role in Vietnamese affairs were reported on an almost daily basis.

“I’m not so sure the ‘playboy’ angle is the best one for Bao Dai,” says historian Dr Christopher Goscha, author of The Penguin History of Modern Vietnam, published last year, pointing out that Bao Dai had a central role in the development of Vietnam during the faltering days of colonial rule.

Had he played his cards differently, Vietnam might not have embraced communism and the second Indochina war (today more widely known as the Vietnam war) may even have been avoided.

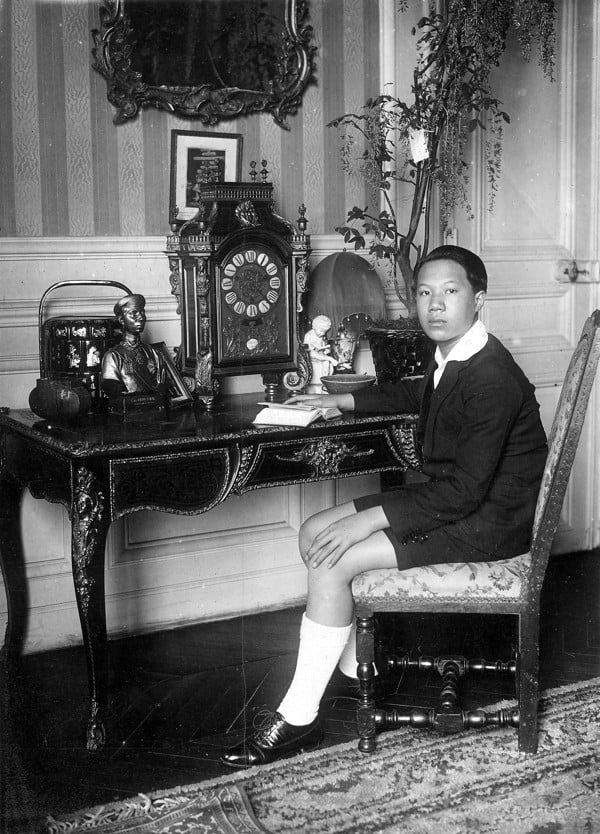

Having just violently suppressed a peasant uprising, the French authorities returned the young king from France – and his studies and sporting pursuits (he was a keen tennis player) – in the early 1930s, introducing the 19-year-old to his people in meticulously choreographed public tours.

The teenage Bao Dai was full of youthful exuberance and naive optimism about national reform and modernisation, according to a variety of sources, but the French soon stifled his ardour for politics.

The young man groomed for office in the finest Parisian schools was paraded like a stooge, and there are many photographs at the Imperial Palace in Hue of the young monarch being escorted past apparently adoring crowds by smiling members of the French military and colonial elite.

But such images may not show the complete picture. “Bao Dai may have been a weak, unpredictable, corruptible playboy, but he was no fool,” writes Karnow. With few other options, Bao Dai chose passive non-compliance in what he saw as a farce, and retreated to Da Lat.

In effect, Bao Dai went on strike for most of his early career. And there was little to occupy him even during the Japanese occupation of Vietnam, from 1941. The Japanese were content to allow Vichy France to continue to administer their former colonies in Indochina. It is unlikely that the two Bakelite telephones on display in his study in Da Lat rang very often, as the French left him to his protracted sulk. The second world war mostly passed him by until March 1945, when he found himself thrust into the centre of political developments.

By early 1945, most observers were predicting an American victory in what was now termed Southeast Asia, and there were rumours of beach landings in central Vietnam, so the actors in Vietnamese politics began to jockey for position.

The Free-French president, Charles de Gaulle, desperate to re-establish French Indochina at the end of the second world war, started moving troops and supplies into the area, ready to assist any United States arrival, but the Japanese responded decisively. On March 9, 1945, they staged a coup and interned all French forces and key officials, shooting any who opposed them.

When Japanese officials eventually tracked down Bao Dai (who was away on yet another tiger hunting trip), they told him that Japan had granted Vietnam its freedom, the days of French rule were over and he was able to declare Vietnam an independent state (albeit under Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere).

Bao Dai thought he had achieved by accident what nationalists and communist groups in Vietnam had been fighting to achieve for decades, and he ordered his prime minister, Tran Trong Kim, to set about tearing down French monuments and prepare for a heroic independent era.

Bao Dai’s optimism proved to be ephemeral, however.

When the emperor of Japan announced his nation’s surrender, in August 1945, Ho Chi Minh’s Indochinese Communist Party seized the moment while French forces were still under lock and key. Ho’s Viet Minh troops mounted what is still known in Vietnam as the “August revolution” and announced the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

His nationalist rivals, while more formidable, were still waiting for Chinese troops to arrive and disarm the occupying Japanese. Few people inside Vietnam, including Bao Dai, had heard of Ho before 1945. Now the wily and fiercely determined revolutionary led the nation.

On August 30, 1945, the playboy emperor was thrust centre stage once again. At the request of Ho, Bao Dai abdicated his throne in a formal ceremony at the Imperial Palace in Hue, so terminating 143 years of Nguyen dynastic rule. The gesture was political dynamite because it indirectly bestowed his royal power on Ho.

“For the first time in his life, France’s colonial emperor had openly challenged the French,” says Goscha, and the colonialists were horrified.

“I would rather be a simple citizen of an independent country than the king of a dominated nation,” Bao Dai is reported to have said.

Before his departure, he sent an impassioned plea to De Gaulle, urging the latter to give up French colonial ambitions in Vietnam as a lost cause.

“Every village will be a nest of resistance, each former collaborator an enemy, and your officials and colonists will themselves seek to leave this atmosphere, which will choke them,” he wrote, correctly predicting the fate of France in Indochina over the next decade.

Despite his worries, Bao Dai did not find himself walking into a trap. In fact, he was impressed by the courtesy with which he was treated by Ho. When he was dispatched on official business to China, in March 1946, however, he chose not to return. He took up residence in Hong Kong and attempted to keep a low profile in exile, as his nation descended into bloody chaos.

Every village will be a nest of resistance, each former collaborator an enemy, and your officials and colonists will themselves seek to leave this atmosphere, which will choke them

On December 19, 1946, the first Indochina war started when French forces, who had been permitted by the Allied powers to re-establish their colony, bombarded Haiphong. The Democratic Republic of Vietnam under Ho responded with a highly effective guerilla campaign.

Non-communist nationalist groups seeking a “third force” in Vietnam beat a path to Bao Dai’s door in Hong Kong, seeking support (as did the French, who desperately needed a local figurehead to lend legitimacy). The result was his collaboration with nationalist groups opposed to Ho’s Democratic Republic in an effort to force the French to decolonise.

“Bao Dai was politically significant during the first Indochina war,” says Goscha. So significant, in fact, that there was a price on his head. On April 19, 1947, the South China Morning Post reported that – due to an alleged murder threat – Bao Dai had been moved to a secret address in Hong Kong.

“It is understood that the local authorities have been asked to round up two persons who recently left Indo-China for Hongkong with orders to remove the former Emperor from the future political picture of that revolt-torn country,” ran the report.

On August 14 of the same year, it was reported that a spontaneous mass demonstration in Hue (probably orchestrated by France) demanded the immediate return of the emperor. Bao Dai “offered his services”, according to a headline in Hong Kong’s Sunday Herald on August 31, but insisted that a precondition for his assistance was a truly independent and unified Vietnam.

On March 8, 1949, Bao Dai was finally convinced by the French that they would concede independence and he signed the Élysée Accords in Paris, becoming head of the new Associated States of Vietnam, in direct competition with Ho’s Democratic Republic. In response, Ho sought and obtained formal recognition for his regime from Mao Zedong’s China and Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union. Bao Dai unwittingly found himself on the front line of the cold war in Southeast Asia and the promised independence never materialised.

“He thought that he could ‘play’ the French but the French played him,” says Goscha.

Belatedly, Bao Dai realised that he had been wasting his time with France from day one and Hong Kong press reports record his reluctance to return to Vietnam to play out the puppet role he despised.

Perhaps, if Bao Dai had not wasted so much energy and credibility negotiating with his colonial oppressors in Hong Kong and led a bold nationalist movement against them, the story of Vietnam and the subsequent second Indochina war might have been very different. Instead, he preferred what Goscha calls “inertia as resistance” at Da Lat, leaving prime minister Tran to sort out day-to-day affairs.

“Rather than turning the monarchy on the coloniser and the communists by leading a crusade for independence, as Norodom Sihanouk [did in Cambodia ...] Bao Dai intentionally let it die,” says Goscha.

After Ho’s victory over France at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, in May 1954, Bao Dai made one last patriotic attempt to bite the hand of his European master by appointing respected nationalist Ngo Dinh Diem as his prime minister, for talks at a Geneva peace convention. Those talks resulted in Vietnam being divided at the 17th parallel and, with American backing, Ngo deposed Bao Dai in a sham election in 1955.

Bao Dai’s outrage made yet more headlines in Hong Kong, but his political role was over. He retired from public life and lived out his days in France, observing the horror of the second Indochinese war (which would drag in the US and last until 1975) from Paris. On his death, Bao Dai was interred in the French capital’s Cimetière de Passy.

Ultimately, though the last emperor of Vietnam failed in his political machinations, and certainly enjoyed the many trappings of entitlement, he was never blind to his circumstances. “We can be sure that whatever Bao Dai’s flaws (and there were many), naiveté was not among them,” writes Goscha, and the playboy emperor had no illusions about his failures and limitations.

Karnow concurs, writing that Bao Dai’s inner circle included a “spectacular blonde French courtesan” billed as a member of the imperial film unit. Once, on hearing her disparaged, Vietnam’s final “keeper of greatness” remarked: “She is only plying her trade – I’m the real whore.”