Susan Schnall still remembers the shrieks of Vietnam veterans that would ring out at Oak Knoll naval hospital throughout the night, as men – some not yet 20 – grappled with the agony of their injuries and the terrible flashbacks of war.

It was these screams, and finding herself – a 25-year-old navy nurse – part of an “unconscionable military machine” that fixed men up only to send them straight back into bloody battle, that drove her to one of the great acts of anti-Vietnam war defiance.

In 1968, Schnall hired a small plane with a pilot friend and showered 20,000 flyers over five army bases San Franscico, including the docked warship the USS Ranger, urging GIs to join an anti-war demonstration two days later.

“I knew that the airforce was dropping flyers on the Vietnamese urging them to get away from the bombing and the spraying of Agent Orange, and I thought, ‘if the United States can do that there, why can’t we do that here?” said Schnall. Her anti-war statement, like so many that came after it, did not come without sacrifice. She was court martialled and sentenced to six months hard labour – though in the end never served her sentence.

Schnall is just one of the dozen of veterans who are visiting Vietnam for the opening of an exhibition that honours the almost-forgotten yet pivotal role that active duty servicemen men and women played in the anti-war movement.

Schnall is one of many who feature in the exhibition, held at the War Remnants museum in the former South Vietnam capital, Ho Chi Minh City. A picture of her leading the GI anti-war march days before she was court martialled will hang in pride of place, alongside newsletters, posters and handwritten letters and photographs, most of which have never been exhibited.

While the stereotypical image of the Vietnam anti-war protester is hippies on campus, flowers in hand, by 1968 every major demonstration was actually led by active-duty officers. Most had returned so horrified by what they had seen and done, they became the most vocal and forceful voices in the anti-war movement.

The exhibition, titled Waging Peace, opens in the midst of the 50th anniversary of the Tet Offensive – a brutal turning point in the war – and will travel to Notre Dame University in the US after Vietnam.

Waging Peace has been curated by Ron Carver, who worked alongside active GIs and servicemen in the anti-war movement from 1968.

For Carver and the GIs involved, telling this story in Vietnam was essential and at the exhibition opening on 19 March the US veterans will meet with their Vietnamese counterparts.

Patriotic duty, then a sense of betrayal

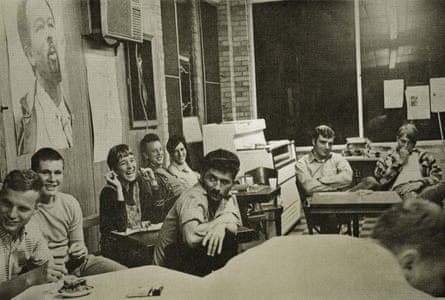

Carver helped in the network of coffeehouses, the beating heart of the anti war-movement, which were casual gathering spaces set up near army bases in the US (an estimated 300 existed across the US). Here, disaffected servicemen and army personnel would share stories of how they had become convinced the invasion was, as Carver described it, “a cruel, terrible thing,”

“A lot of these soldiers felt very angry,” said Carver. “Many of them had volunteered to go into the military thinking it was a patriotic and righteous thing to do, and when they went over there and saw the Vietnamese population did not want us, saw the brutality and the war crimes that our country was committing, they felt very betrayed and were highly, highly motivated to develop resistance.”

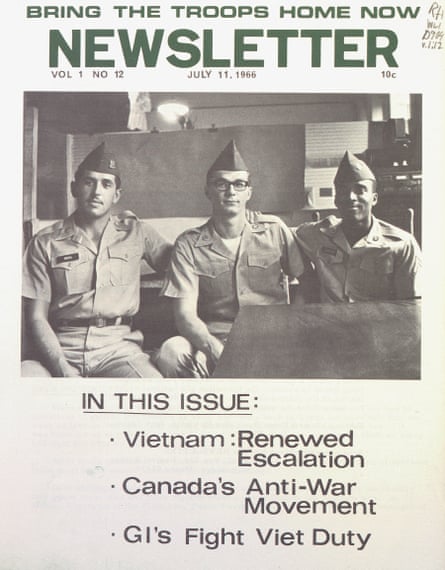

It was not just conversation that came out of these coffeehouses. They were the hubs of the underground newspapers that proliferated during the war, filled with firsthand accounts from GIs of brutality from the frontline and telling a truth the government and the military tried to suppress. It was often a DIY operation by the GIs who would put the newspapers together by hand and then photocopy them.

They form a focal part of the exhibition. It is thought there were more than 5,000 underground newspapers at the height of the anti-war movement. In San Francisco, The Ally newspaper, which came out monthly, printed up to 20,000 copies each time, and they shipped batches of 100 to the soldiers in Vietnam, where they were a core part of the discord that erupted across military bases.

The military fought back against the coffeehouses as best it could, using police to shut down them down and punishing GIs if they were found in possession of newspapers. They were even investigated by the FBI and, in Fort Dix, the coffeehouse was bombed by vigilantes.

Yet the army came down heaviest on those whose anti-war statements were made in public defiance of orders. Among those honoured by the exhibition are the “Fort Hood Three”, a trio of soldiers who were drafted and trained but refused to report for duty in 1966. It landed them with a court martial and a three-year jail sentence, but as newspapers and posters in the exhibition reveal, they were also made into martyrs by the GI anti-war movement.

“ I really began to identify with the struggle of the Vietnamese people and I began to admire them,” said JJ Johnson, one of the Fort Hood 3. “And the strength to resist grew from the knowledge. I realised, ‘to hell with them, I can’t take part in this.’ And we wanted to say it publicly so people knew this was a feeling that exists within the military.”

The exhibition acknowledges that not all the sacrifices were purely public. Chuck Searcy, who worked with Carver on the exhibition, spent a year in military intelligence in Saigon in 1968 and came back vehemently against the war. He began to speak out, but was subsequently disowned by his father, a former World War Two veteran, and estranged from his family for two years.

“My parents were dismayed,” he said. “It was embarrassing to them. I remember my father said ‘you’re not a good American, you’re not a patriot any more.’ He said to me, ‘what happened to you over there, did they turn you into a communist?’ So many families went through that.”

Schnall, Johnson and Searcy all agreed that despite the multitudes of books and documentaries on Vietnam, the role that GIs played in fighting for peace from within has always been downplayed and overlooked.

“People need to know that active duty soldiers at the height of the Vietnam war, in the belly of the beast, the belly of the green machine, were able to build a movement that ended up crippling the ground forces and stopped them being effective,” added Carver. “That should be an inspiration to people, and that’s what it’s all about.”

- Waging Peace: US Soldiers and Veterans who Opposed America’s War in Vietnam opens on 19 March at the War Remnants museum in Ho Chi Minh City.